The female and the feminine in Dracula and The Woman

in White.

‘Different

though the sexes are, they intermix. In every human being a vacillation from

one sex to the other takes place, and often it is only the clothes that keep

the male or female like-ness, while underneath the sex is the very opposite of

what is above. Of the complications and confusions which thus result every one

has had experience’

One must assess the distinction between the

biology and psychology of gender; an individual’s gender is distinguished by

their dress and outward appearances. It is not until the reader and other

characters get a closer look to discover that often their psychology and

personality have characteristics of both genders- it is in this way that many

characters in Dracula and The Woman in White transgress traditional gender

roles.

What separates

the masculine and the male, the feminine and the female in these two novels and

how characters, male and female often move about between them.

Jonathan Harker declares the gender of the

three vampiric women in Dracula’s castle; they are clearly ‘ladies by their

dress and manner’ this assumption is soon proven wrong, he hears ‘the churning

sound of [one of the women’s] tongue as

it licked her teeth and lips, and [he] could feel the hot breath on [his]

neck.’ Like a fire-breathing dragon she

asserts her masculine power over him. This strong presence causes Harker to

faint, the horror ‘overcame [him] and [he] sank down into unconsciousness’;

this can be contrasted to Mina who is ‘not of a fainting disposition’. By

fainting Harker’s response corresponds with a typically feminine role to pass

out, the shock of his experience proving too much for him. He expresses that

‘there was something about them that made me feel uneasy, some longing and at

the same time some deadly fear. I felt in my heart a wicked burning desire that

they would kiss me with those red lips’ This is an example of fear versus

desire that is common throughout the two novels to define masculinity and femininity,

it would normally be the powerful male asserting his power and the weaker,

passive female desiring him. Harker here takes on a passive role; and the

masculine female takes control of the feminine male. This mechanical likeness

of the ‘churning tongue’ removes any emotional connections to a woman the

reader may have these women are no longer feminine, or even female, they

transgress so completely out of femininity that they cannot even be classed as

males, perhaps only as ‘monsters’.

Tori Moi in Sexual/ Textual Politics coins

the term ‘monster woman’ not as a reference to the literal supernatural monster

of Gothic fiction but to describe the ‘new woman’ that Mina Harker and Marian

Halcombe can be likened to. This ‘monster woman’ ‘is the woman who refuses to

be selfless, acts on her own initiative, who has a story to tell – in short, a

woman who rejects the submissive role patriarchy has reserved for her’ by

remaining a single woman and taking an active role in the discovery of the

identity of the mysterious woman in white, Marian does exactly this. Moi goes

on to explain that ‘the duplicitous woman is opaque to man, whose mind will not

let itself be penetrated by the phallic probings of masculine thought’.

Dracula,

by using feminine terms to describe him – is not the masculine, phallic power

Moi describes, that is more like Sir Percival, of even Count Fosco. Although

Dracula invades Mina’s mind he does not control it, Dracula’s femininity allows

Mina and the men to use it to their advantage. As easily as Dracula changes

from old to young, he shifts from masculine to feminine. Like ‘a child forcing

a kitten’s nose into a saucer of milk’ he maternally feeds his blood to Mina, although it has darker undertones, this

image comes across as feminine; as if he is feeding Mina for her own good.

Conversely Dracula has the potential to be a powerful and dangerous man, his

eyes ‘blazed with a sort of demonic fury’ at the sight of Harker’s blood on his

chin, he uncontrollably ‘[makes] a grab at’ Harker’s throat. Dracula is the

only character who is able to change so quickly from feminine to masculine

without any noticeable changing process; possibly because he lacks humanity he

therefore lacks any gender stability.

The

male desire to assist a damsel in distress throughout Dracula and The Woman in

White.

Hartright,

upon his first meeting with Anne notes that ‘the loneliness and helplessness’

of her affected him, ‘the natural impulse to assist her and to spare her, got

the better of the judgment, the caution, the worldly tact, which an older,

wiser and colder man might have summoned to help him in this strange

emergency’. Reason and rationality are overridden by the desire to help the

weak, and the helpless; here are conflicting masculine impulses. Hartight acts

upon his urge to be ‘the knight in shining armour’ that many of the male

characters in the novels aspire to be. Even Mina, one of the stronger female

characters, is subjected to this impulse, the men around her feel the need to

protect her and do not consider that she may, in fact be able to protect

herself. Dr Seward notes that ‘I must be careful not to frighten her’ immediately making the assumption that Mina conforms to the typical feminine

role as Lucy does and requires, for her health, censorship. He later states

‘Mrs Harker is better out of it. Things are quite bad enough for us, all men of

the world, and who have been in many tight places in our time; but it is no

place for a woman’ despite her efforts to act like a man and to be part of the group as an equal,

Mina’s womanly physical appearance blind the men into treating her and

protecting her as a woman should be.

In her diary, Mina does not separate the

masculine and feminine but instead distinguishes between good and evil, light

and dark. As she looks towards Whitby Abbey Mina sees Lucy, a ‘half reclining

figure, snowy white’ and a ‘man or beast’ ‘something dark’ leaning over her

in a domineering fashion. This is reminiscent of Harker’s experience in

Dracula’s castle – a powerful, overbearing masculine force, bent over a

powerless body - and has highly charged sexual connotations; Count Dracula is

forcing himself upon her as the three women forced themselves upon Harker. The snowy white figure of Lucy agrees with

the general view that white signifies innocence. In The Woman in White the

reader is in someway led to reassess such connotations – once we learn that the

strange figure of the woman in white has escaped from and asylum we make links

with the whiteness of an asylum, of medicinal sterility of straight jackets and

padded walls. At this moment in time, for the reader and for Hartright these

connotations overpower that of innocence, so as to make him become suspicious

or even frightened. The reassessment of the traditional symbolic meaning of

white happens in Dracula too where whiteness/ paleness instead takes on the

negative meaning of bloodlessness.

The uses of light and dark in The Woman in

White draw contrasts between the women, rather than between good and evil. Anne

is too white; her skin is deathly pale, and her strange habit, commented and

teased by Mrs Clements of wearing all white makes other characters wary of

her. Hartright describes her as having

‘a colourless, youthful face, meagre and sharp to look at about the cheeks and

chin; large, grave, wistfully attentive eyes; nervous uncertain lips; and a

light hair of a pale, brownish-yellow hue’.

She comes across as too weak, and too fragile; this is an extreme of the

Victorian female gender role. Collins could be commenting on the position of

women in society and if one should take their position as a weak passive female

too far they must prepare for negative consequences. This can be compared to

Hartright’s description of Laura Fairlie; she is light, beautiful, ‘her hair is

of so faint and pale a brown- not glossy- that it nearly melts, here and there

into the shadow of the hat’ and her eyes ‘of that soft, limpid, turquoise blue,

so often sung by the poets, so seldom seen in real life’ the features

damned in Anne are praised in Laura; this description could be foreshadowing

her downfall when mistaken as Anne. When Laura loses her identity and becomes

Anne catherick she too becomes ghostly white – brought upon by the asylum. The

dark, ugly Marian has more character, she is unusual and intriguing to the

reader, Hartright’s first impression of Marian is ‘the lady is dark’, he

describes ‘the lady’s complexion was almost swarthy, and the dark down on her

upper lip was almost a moustache. She had a large, firm, masculine mouth and

jaw; prominent, resolute, piercing eyes’ This is a very masculine description and unlike Mina, who has to fight against

her feminine appearance to prove her worth as her own person, Marian is

immediately confided in by Hartright, it could be argued with help from her

not-so fragile appearance, about his strange journey to Limmeridge house.

Harvey Peter Sucksmith, in the

introduction to the Oxford University Press publication of The Woman in White

explains the reason for, in his view, one hero and two heroines; he draws a

parallel between Hartright and the author’s own personal experiences - ‘we can

see now why there are two heroines inn the novel but only one hero, for Collins

achieves psychological validity with this trio by representing in Victorian

terms what have been called the anima and the shadow, that is, here, the

Victorian male’s idealised image of women together with much of a contradictory

nature that is excluded from that ideal. Collins, the man who later lived with

two women, depicts a hero who experiences the dual nature of women’.

Sucksmith suggests that Collins simplifies woman into two forms for the sake of

clarity for the reader. This can be taken that in this case one woman with both

attributes would not be effective; that men may be able to freely display both

sides of their nature, but women, in order to make sense in a Victorian novel

and in society, must be separated into two characters. Stoker on the other

hand, creates Mina of whom Helsing exclaims has a ‘man’s brain – a brain that a

man should have were he much gifted- and a woman’s heart’ This perhaps is

a better image of the ideal ‘new’ woman who happily displays feminine and

masculine attributes.

The mouth is often described as both cruel

and voluptuous in Dracula; ‘all three [vampire women] had brilliant white teeth

that shone like pearls against the ruby of their voluptuous lips.’ These images of pearls and rubies connote richness and abundance, as if Harker

is attempting to dress up the bad, masculine imagery in feminine jewellery. The

word voluptuous is often repeated by Stoker, and becomes a word loaded with

dark, sexual connotations. Lucy, at the beginning of the novel ‘so sweet and

sensitive that she feels influences more acutely than other people do’ becomes evil and voluptuous - Stoker uses this word to describe Lucy as many as

four times within two pages, ‘the sweetness was turned to adamantine, heartless

cruelty and the purity to voluptuous wantonness’. The site of the

burial place is a place of transgression from the feminine to the masculine for

Lucy; it is at her tomb that Lucy re-awakens as a vampire. Her whole appearance

changes, without any maternal instinct she preys on small children and is an

aggressive hunter, as if she has been re-born; Lucy’s eyes, the windows to her

soul, ‘the beautiful colour became livid, the eyes seemed to throw out sparks

of hell-fire, the brows were wrinkled as though the folds of the flesh were the

coils of Medusa’s snakes, and the lovely, blood stained mouth grew to an open

square….as if ever a face meant death- if looks could kill- we saw it at that

moment’.

The transformation is quick and is a movement from extreme good to extreme

evil. There is a link between the transition between life and death, between

masculine and feminine at a place of burial, this verifies Victorian

stereotypes of the weak women in neither novel do any male characters die so

never get chance to move across from femininity to masculinity or vice versa as

harshly as Lucy.

The tomb and the grave, is a key setting

in both novels, it is a place where the lines between life and death are

blurred. It is where the body of Anne Catherick is buried, but as Laura. At the

climax of the novel; the supposed dead Lady Glyde appears next to her very own

grave – the dead and the living (the very same person) standing side by side.

This is where the physical and the psychological play a part; Laura is

identified as Anne by her clothes, by her appearances only. Marian and Hartright

therefore become ‘accomplices of mad Anne Catherick, who claims the name, the

place and the living personality of the dead Lady Glyde’ Laura has completely lost her identity; she

claims ‘they tried to make me forget everything’ although her insistence

of her true identity is pushed aside and ignored over her appearance- she is in

Anne’s clothing therefore must be Anne. Collins draws light upon the thin line

between the sane and insanity. Insanity has a strong historical link with

females, female stepping out of place in society were reported as having

hysteria and that the label of insanity more often than not were restrictions

put on by men to keep unruly women in line which can be seen in Sir Percival’s

treatment of Anne. Harker once again becomes the feminine male, he reported as

hysteric and labelled mentally ill and

thus questions himself, ‘I feel my head spin round, and I do not know if it was

all real or the dreaming of a madman. You know I have had a brain fever, and

that is to be mad’.

Harker’s so called brain fever places doubt in the reader’s mind; fact and

fiction becomes intermingled, at this point in the novel even the reader is led

to question the authenticity of Harker’s diary. It is the only source of

information that Mina and the reader have to rely upon. It is at this point in

the novel that the reader instead of using Harker as the assertive, trustworthy

voice – turns to Mina.

The

main female characters often become frustrated with their gender throughout the

course of the novels.

Both

Mina and Marian become angry at their sex for restricting them, they are well

aware of the social implications of being female in Victorian society. Nobody is more aware of

the divide between the sexes than Marian, she orders Hartright not to ‘shrink

under’ his feelings for Laura ‘like a woman’ but to ‘tear it out, trample it

under like a man’, angry at Hartright for not using his male advantages. After

all she would be expected to shrink under her feelings, though when she does,

when she cries ‘miserable, weak, women’s tears of vexation and rage’ she is angry at herself for showing signs of weakness out of sheer frustration

that her sex allows her to do nothing else. Gentle Laura, noticing her sister’s

lapse of strength ‘put her handkerchief over my face, to hide for me the

betrayal of my own weakness- the weakness of all others which she knew that I

most despised’ Marian is an alternative of womankind; she defines a different type of

femininity to that of the Victorian stereotype. Susan Balée suggests an

alternative opening line to The Woman in White: that Hartright is instead a man

with a woman’s patience and Marian is a woman with a man’s resolution.

Dracula and The Woman in White are

interested in examining what lies beneath appearances of gender, Collins adopts

a more obvious approach by splitting two versions of the female in Laura and

Marian – both in appearances of fair and dark and in characteristics, mentally

weak and strong. Stoker combines these in the character of Mina – he does have

a stereotypically feminine female that is Lucy who transgresses from being

extremely feminine to extremely masculine. Both authors question the Victorian

masculine and feminine roles and how males and females fit into them, and if

there is any room for manoeuvring.

A little help from...

Stoker,

Bram – Dracula (Penguin Popular Classics: 1994) London.

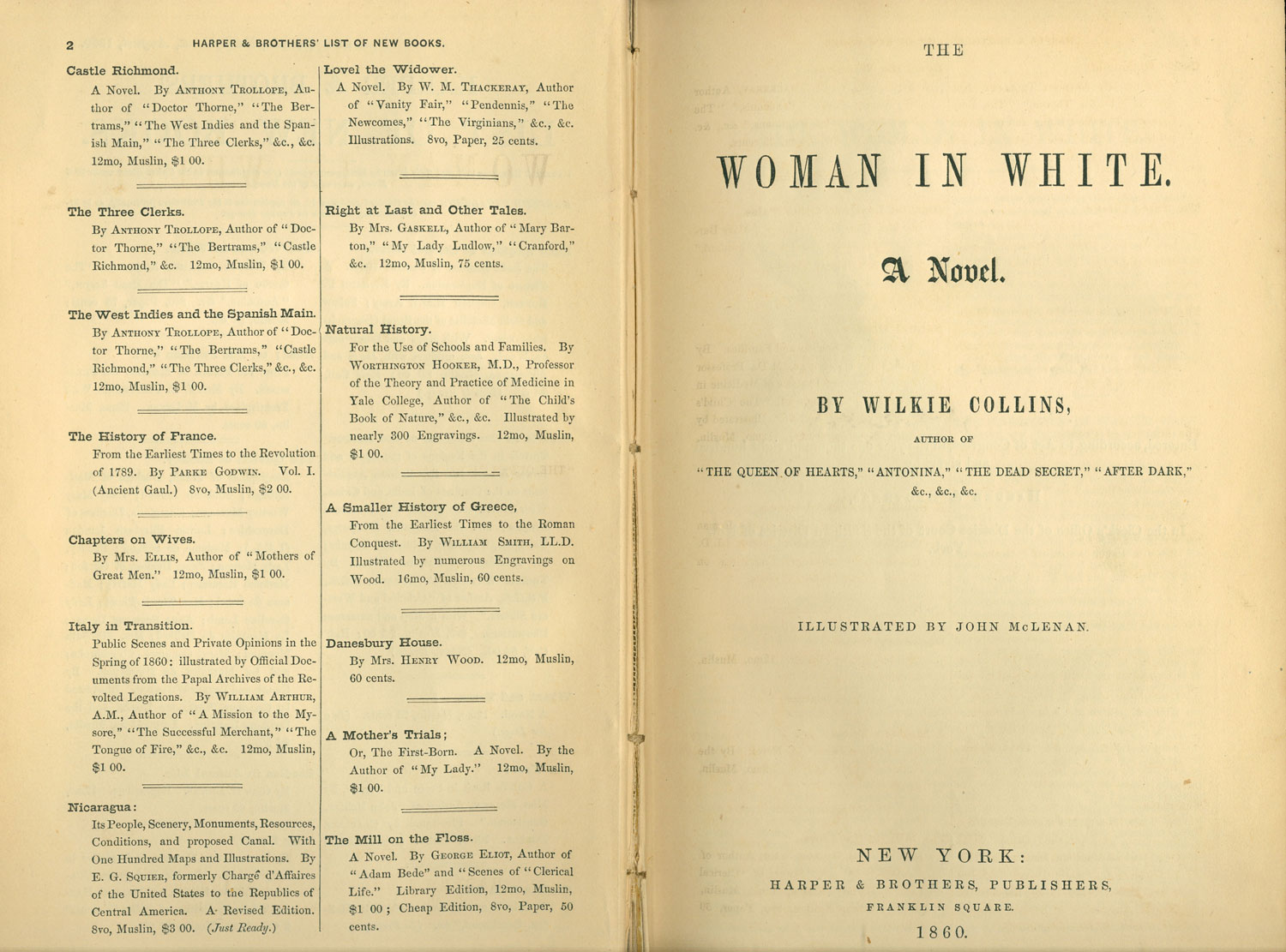

Collins,

Wilkie – The Woman in White ed. Harvey Peter Sucksmith (Oxford University

Press: 1975) New York and Toronto.

Woolf,

Virginia – Orlando (Oxford World Classics: 1998) Oxford.

Moi,

Tori - Sexual/ Textual Politics:

Feminist Literary Theory (Routledge: 1999) London and New York

Jacobus,

Mary – Reading Women: Essays in Feminist Criticism (Columbia University Press:

1986)

Balée,

Susan – ‘Wilkie Collins and Surplus Women: The Case of Marian Halcombe’ Victorian

Literature and Culture. (Cambridge University Press:1992) Vol. 20 pp.197-215

Miller,

D.A – ‘Cage Aux Folles: Sensation and Gender in Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in

White’ Representation, No.14, The Making of the Modern Body: Sexuality and

Society in the Nineteenth Century pp. 106-136

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2928437.

Demetrakopoulos,

Stephanie – ‘Feminism, Sex Role Exchanges, and Other Subliminal Fantasies in

Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”’ Frontiers: Journal of Women Studies (1977) Vol. 2, No.

3 pp.104-113

Craft,

Christopher – “Kiss me with those red lips”: Gender and Inversion in Bram

Stoker’s Dracula’ Representations No8. (1984) pp107-33

http:/www.jstor.org/stable/2928560